Introduction

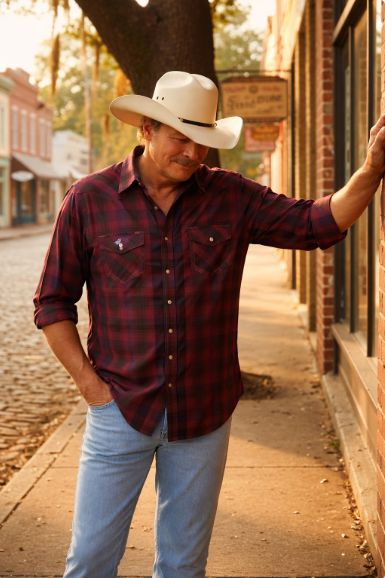

Red Dirt Reverie”: Why Alan Jackson’s Walk Through Old Georgia Feels Like a Song You Can See

There’s a certain kind of moment that doesn’t need cameras, crowds, or commentary to feel important. It’s the kind of moment that older people recognize instantly—because it’s the moment when life circles back and quietly asks, Do you remember where you began? That’s why the line “At 67, Alan Jackson walked those old Georgia streets like he was touching memories with his own hands. Nothing fancy. Just the red dirt, the quiet air, and the place that made him who he is.” feels less like a caption and more like the opening scene of a country ballad that never really ended.

Alan Jackson has always been an artist of place. Not “place” as a postcard, but place as a teacher. In his music, geography isn’t scenery—it’s character. The red dirt isn’t just dirt; it’s the color of work boots, baseball fields, church parking lots, and long days that shaped people before they had the luxury of explaining themselves. The quiet air isn’t emptiness; it’s the space where you can finally hear your own thoughts, and where the past rises up gently—sometimes comfortingly, sometimes painfully—because it still knows your name.

The phrase “touching memories with his own hands” is especially telling for mature readers. At a certain age, memory stops being a simple slideshow and becomes something physical. It lives in the body. You can feel it in your chest when you pass an old house, in your throat when you smell rain on warm pavement, in your knees when you walk a road you once ran down without thinking. That’s the truth this image captures: going back home isn’t only mental. It’s sensory. It’s the world reminding you who you were before you became who everyone else thinks you are.

And then there’s “nothing fancy.” Those two words are practically a mission statement for Alan’s entire legacy. He never built his career on being the loudest voice in the room. He built it on being the clearest. He sang about ordinary life with uncommon respect. He made room for modesty, humor, faith, heartbreak, and pride—all without turning them into spectacle. So picturing him walking old Georgia streets, without fanfare, makes emotional sense. It’s not a publicity stunt; it’s a return to the source.

For older, educated audiences, this kind of scene is moving because it reflects something universal: the desire to confirm that your beginnings were real, that your roots still exist, and that time—despite everything it changes—cannot erase the places that formed you. There’s also a quiet courage in it. When you revisit the ground that made you, you’re not only remembering the good. You’re remembering the hard. You’re remembering what you survived, what you learned, and what you lost along the way.

That’s why “At 67, Alan Jackson walked those old Georgia streets like he was touching memories with his own hands. Nothing fancy. Just the red dirt, the quiet air, and the place that made him who he is.” works as an introduction to a song, a story, or a chapter in his life. It sets the tone for something honest: a reflection on home, identity, and the kind of legacy that doesn’t need glitter to shine. Sometimes the most powerful music begins exactly like this—one man, one road, and the silence that says more than applause ever could.